INSIDE WW 2 MANZANAR, PART 3

After checking the human manifest the officials gave the green light to ”the great iron monster’ which lurched forward and slowly started to roll. We missed the familiar courtesy cry of the conductor’s “All Aboard” which made this cold scene even more lonely and depressing. As we passed the once-famous Union Station I caught a glimpse of the towering city hall which would be my last for a long time to come. To a number of young men in our group who were later killed in action while serving with the 100th Infantry this was a final farewell to a landmark..

One by one the taller buildings slowly disappeared from view as the train made its way around the bend through the industrial section of Lincoln Heights. A few casual onlookers peered over the overpass railing to catch a glimpse of our “Grand Exit” from their city. “No flowers, no speeches, no fanfare.” We left the city as “quietly and orderly” as we had lived. One evening recently as I watched the closing scenes of “Fiddler on the Roof” on television I couldn’t help but relive the past and feel the hopelessness of a similar situation we had experienced 32 years ago. The forced evacuation of the Russian Jews from Russia was of a much earlier era, but the problems and heartaches created by the government and its political bodies must surely remain the same.

This action was reminiscent of the controversial decision that faced the Japanese American Citizens League in their role as mediators and spokesman for some 110,000 citizens and non-citizens on the west coast. Their final decision and the endorsement of the mass evacuation of all Japanese from this vital defense zone may or may not have prevented unavoidable incidents. (Isolated cases of beatings were reported.) Some felt that our own JACL was selling us down the river…..

The train picked up speed and the sights of the city and its familiar skyline faded in the distance. Choked up and misty-eyed, I leaned back into the hard seat of the day coach and closed my eyes for a moment as the reason for me and my family being on the train became painfully evident. I couldn’t accept the fact that we were leaving our friends and our homes, labeled as enemies of our country. In all of my recollections from my early youth, I had always portrayed myself as the herd-type, the good guy, the knight in shining armor, and now, I found myself rudely shoved into the unfamiliar role of the bad guy. There would have to be a lot of changes made for I wasn’t prepared to accept it. Our unknown destiny behind us, leaving our childhood dreams, our hopes, our very lives, Our future now was in the hands of America,

The sun burned up the early morning mist and as the day grew warmer, the general mood among the passengers lightened as the light happy chatter of the children started to fill the car. When the box lunches consisting of sandwiches, fruits and cartons of milk were distributed by the MPs, I was asked to help. It was a great ice-breaker for me as it gave me the opportunity to move around the car and meet and chat with the other passengers. I soon realized that I was not alone in this situation as I had imagined.. As I moved about the car cheering people up I strangely found relief of my own. I immediately made new friends in Kow Maruki, Joe Nakai, Lillian Igasaki (she was pretty) and a few others. I met and played baseball with Lillian’s uncle later in a concentration camp in Amache, Colorado. (Story on Amache later.)

As we neared an unknown junction the MPs going from car to car instructed our guards (two guards with rifles in each car) to have us draw our shades during the switching of cars. Apparently the fear of “white Indians” surrounding and circling the train, whooping and hollering in their hopped-up ’36 Fords and attacking “the yellow pioneer settlers.” I stole a peek from behind the blinds only to find a few passerbys who had stopped curious to the drawn shades. I did see small groups of “real Indians” huddled along the side of the station so I assumed we were in the desert country somewhere. We were to find out later that it was the town of Barstow.

After a few hard bumps accompanied by the banging of heavy metal couplings, the engine hissed out a blinding cloud of steam and we were on our way again. The remainder of the train ride was very monotonous and uneventful with sand, bushes and mountain ranges As far as the eye could see. Being unfamiliar with the geography of Eastern California I was at a complete loss to our general location.

We had been informed earlier that the camp was located somewhere in the middle of a desolate desert and in all appearance the rumors were bearing out true. I could almost envision myself as an Indian sitting on a camp stool in front of a canvas (modern Indian) tee-pee. I would have a heavy wool Scotch plaid car blanket draped over my shoulders to ward off the cold winter winds as I Teriyaki-ed jack rabbits and chipmunks over a Coleman stove.

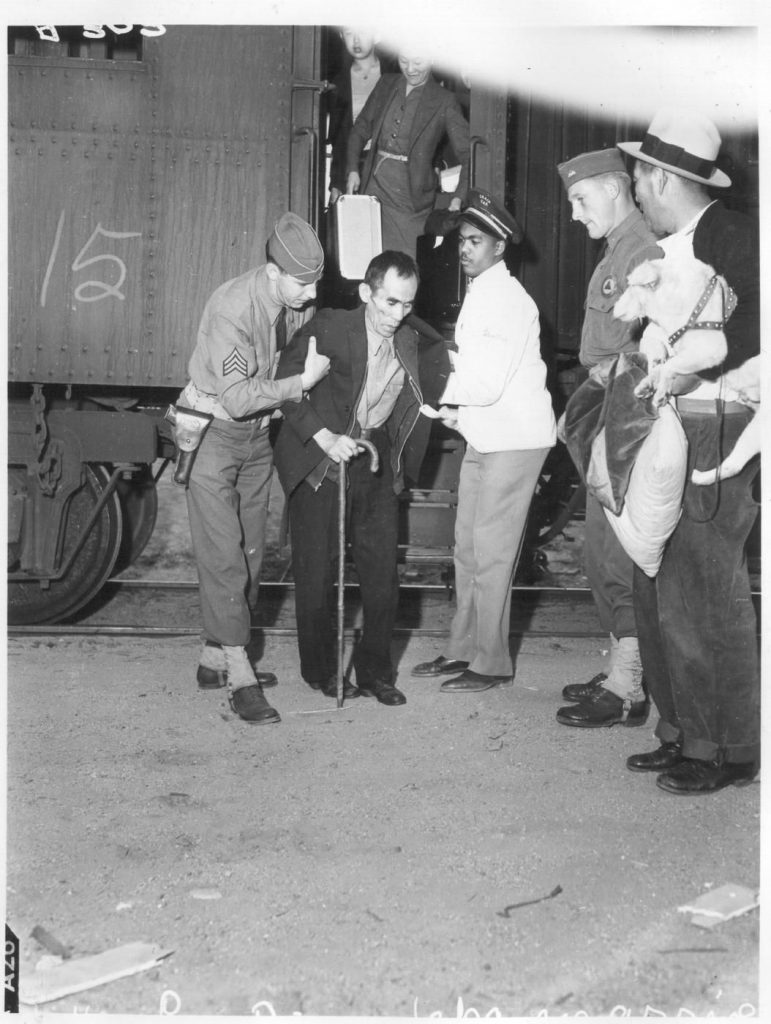

We reached our transfer point outside of a town called Lone Pine sometime during mid-afternoon. Awaiting us were more military personnel and city officials and it was a toss-up whether to be insulted or honored. As we alighted from the train we were greeted by a light to medium wind which was only a sample of what we were to encounter before the day was over. We grabbed our hand baggage and prepared to board the many Greyhound buses which had been activated to take us on the final leg of our journey. Having learned well from their first encounter, the guards warned us to stay together in family units. The passengers welcomed a slight delay while the luggages were transferred to trucks as it gave them a chance to stretch their legs. Carefully grouping us by seat count the guards (some of the guards had mellowed) assisted the old and the young into the buses as there was a mild scramble for the window seat by the youngsters.

After what seemed like hours the caravan of buses rolled onto the highway and headed for our destination, Manzanar. The hum of conversation and excitement mounted as the passengers sensed that the traveling ordeal was nearing its end. To the right of us was the Inyo Mountain Range everchanging its cloak of colorful hue as the sun sets each evening. To the left of us was the towering snow-capped peaks of the majestic Sierra. One of the most impressive sights and also one of the most unforgettable. Most of the camp days artists used this scene as a background for their pictures. Strangely many snapshots (cameras were taboo in camp) showed up with the Sierra as a back drop,

It seemed like we had just settled back comfortably in our seats (the only decent part of the trip) when the bus driver stated as a matter of fact to those within earshot that the camp would soon be visible. As the word spread throughout the bus excitement mounted as everyone strained forward to catch a glimpse of their future home.

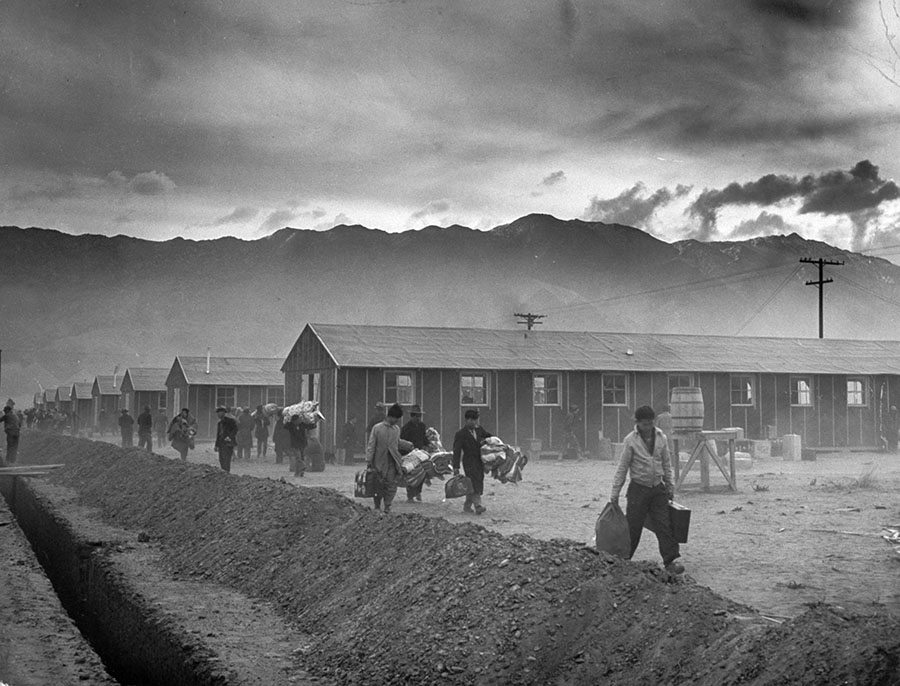

Shortly, we saw what appeared to be at first a great ball of dirty fog off in the distance. but as we approached the camp, it turned out to be one big massive dust storm kicked up by the famous Manzanar wind. We were soon engulfed in it and with visibility near zero the buses turned off Highway 395, moved past the guard house and into camp. We never saw the guard towers with mounted machine guns nor the barbed wire fences till the next day although we experienced the probing searchlights that first night. The strong wind picked up rice-sized sand from the construction area and pelted the sides of the buses like buckshot as it made its way past the barracks.

The buses lined up in the middle of a firebreak between blocks 14 and 15 and we were greeted by the earlier arrivals who in spite of the wind were out to see if their friends or relatives were aboard. They were bundled up in a comical array of World War I surplus GI Army uniforms which were issued by the WRA. What a motley looking lot! Like a bunch of refugees, hardly recognizable. In the following weeks we would be there dressed the same as we greeted each new arrival in our stylish “olive drapes” of baggy pants, hanging jackets, wrap around leggings, helmets, goggles and the whole works. Who was it that said “they all look alike?”

After alighting from the bus, we were directed to mess hall #15 to be registered and to be assigned apartments and army blankets. We were assigned apartments according to size of family and couples without children were forced to share apartments with only sheets or bedspreads, makeshift partitions were put up for a minimum of privacy separating total strangers. This was very embarrassing and degrading situation for most of these unfortunate people. Although we were cramped with six adults in a small room we were of one family which made living endurable. Later as the pieces of the puzzles started to fall in place better arrangement and accomodations were provided for the comforts and the necessities of the residents. Naturally, this did not come about immediately which was par for the course but as time went on, people became hardened to the situation and they themselves went about making living conditions more bearable.

As we will be exposing some of the happenings and the experiences of myself and others, undoubtedly there are and will be other versions of the camp, the life and its views as there are former camp inmates (approx. 110,000). My articles may arouse differences and discrepancies as even my own eyes, left from right, may differ in their observation.

Shiro Nomura, Museums Department Historian for Manzanar