INSIDE MANZANAR DURING WORLD WAR 2

I was made an offer I couldn’t refuse when Henry Raub suggested I write a series of articles on the inside story of Manzanar for the new MUSEUM NEWS BULLETIN. I shall offer my views as a former “inmate” because it offers me the opportunity to inform the readers the Who,,Where, When and Why of Eastern California Museum’s Manzanar camp display. I hope to be able to answer some of the questions in the minds of those who may be concerned.

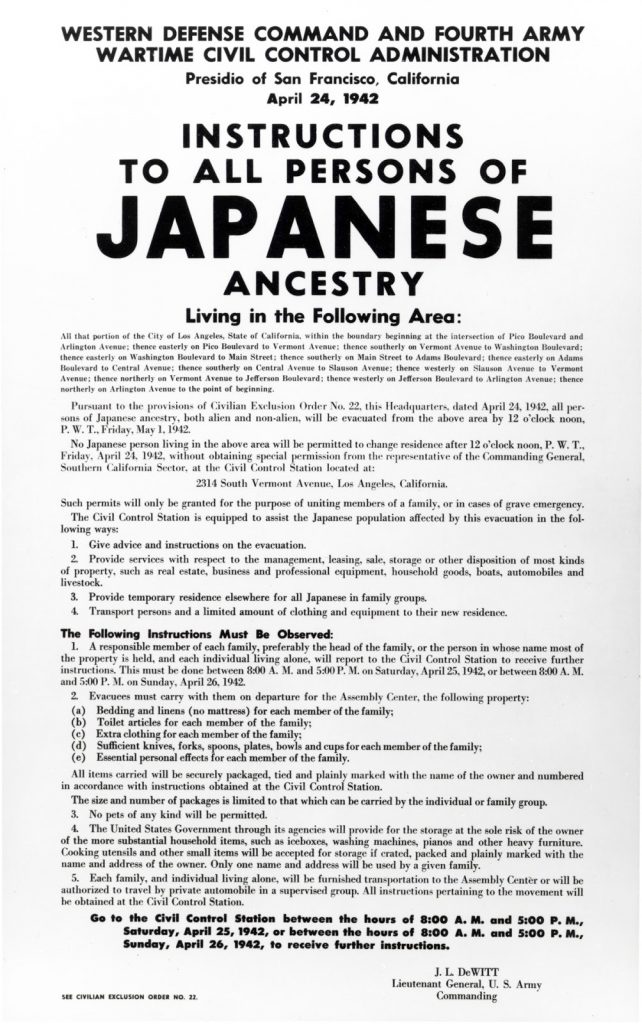

It also gives me the opportunity to relive and relate some of the memories which I’m certain will arouse and disturb some of the sleeping ghosts of a nightmarish past. Many happy memories are also etched in my mind. My recent acquaintances refuse to believe that such an order (mass evacuation) had been passed to initiate the need for a camp such as Manzanar and many others like it. Two camps in Poston, Arizona; two camps in Gila, Arizona, a camp in Idaho; two camps in Arkansas; another in Colorado and Wyoming were some of the major areas of concentration of displaced citizens and aliens alike.

Firmly believing that the “Manzanar Incident” was most vital to the history of inyo County and also to the eyes and ears of a nation indivisible, Directory Henry Raub has been working tirelessly to beg, borrow and wheel and deal to gather and acquire tibits and pieces from former camp inmates and local residents. From the old campsite where only the whispers and echoes of days long past, where sobs and laughter of our yesteryears whistle eerily through the grotesquely disheveled branches of the pear trees, Henry has spent many hours hunting for “treasures” with which he hopes to enhance his camp display.

The first of the camps, Manzanar, which literally sprung up overnight in the middle of a desert wasteland in the spring of ‘42 surely couldn’t have been on the drawing board too long. The haste in which the “wheels of evacuation” was set into motion makes one wonder if the army hadn’t already been prepared with a printed manual on mass evacuation of “enemy aliens.”

My nephew was one of the original Japanese volunteers recruited soon after war was declared with Japan. They had been promised good pay, (we’ll go into that later) good positions and many other priorities which never materialized. Under the supervision of government employed Caucasian contractors, the so-called future living quarters for the American citizens who’s only apparent crime was their Japanese ancestry, started to take shape.

A barbed wire fence was immediately strung the width and breadth of the area marked off like the fence erected to keep the cattle from wandering beyond the “no, no” zone, Guard towers taller than the tallest tree in the area were the next to come up with machine gunes and searchlights, with the power of a “zillion headlights.” It was jokingly said that the street lights of Lone Pine were turned off at night because the searchlight beams of Manzanar kept the town well lit.

A hardy group was the special rattlesnake crew, Members preceded the sagebrush crew clearing the area of snakes so they could prepare the desert land for the barracks to be built. Water pipes were laid, the sewer system was developed, electric and telephone lines were strung and the area within the barbed wires soon took on the appearance of a large army camp. Really a very monotonous sight with identical tar papered barracks to a block and a very large “messy-hall” for each. Thirty-six blocks of living quarters were available after completion. Imagine, our waiting in line for occupancy–”cheap rent.”

On U. S. Highway 395 trucks became a common sight to local residents as building materials and supplies were rushed in to “slap together the future home for the displaced people from the west coast. Ten thousand to be near exact and it has gone on record as the town or community with the largest population in Inyo County. Most of the towns on “395″ are only about a “blink” long, but many travelers during the existence of Manzanar will attest, the length of time it took to travel from one end of te camp to the other took more than 10 blinks of the eye. I know because I walked it many times. (on the inside, of course.

I recall spending the early days in camp trying to understand the circumstances which led to our ”incarceration behind barbed wires.” What had we done to deserve it? The freedom enjoyed and taken so much for granted had suddenly been stripped from us with some signatures on the bottom line of a lot of legal words in small type. Was the teaching of democracy from grade school so shallow and meant only for others? Were my neighbor’s really so sad to see us leave, or only waiting to pick up what we were forced to leave behind? Our stored belongings disappeared. Who were my real friends? With the highway (so near) paralleling the camp, we could sit by the fence looking out at the unchanging landscape, pondering over the many unanswered questions running through our minds. The cliche “so near and yet so far” must have been born inside manzanar. The cars and buses, close enough to touch wood teasingly slow down, curious to the activity in our camp.

There was a little town to the south of us called Lone Pine and I used to relate to it with the “lonely-pining” feeling that I felt. Later, I used to go out to a high Vantage Point outside of camp (escapades–later issue) to watch the night lights of a town just north of Manzanar. How I used to long for a hamburger and a cool tall malt (and yet so far) which I know youths of my age were enjoying. The name of the town? Or yes, it was INDEPENDENCE!